Battle of the Chesapeake

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American War of Independence that took place near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 1781, between a British fleet led by Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves and a French fleet led by Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse. The battle was tactically inconclusive but strategically a major defeat for the British. since it prevented the Royal Navy from resupplying or evacuating the blockaded forces of General Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia. It also prevented interference with transport of French and Continental Army troops and provisions from New York to Yorktown. As a result, Cornwallis surrendered his army after the Siege of Yorktown, the second British army to surrender during the war. The major consequence of Cornwallis's surrender was the beginning of peace negotiations that eventually resulted in British recognition of the independent United States of America.

Upon learning that de Grasse had sailed from the West Indies for North America, and that French admiral de Barras had sailed from Newport, Rhode Island, Admiral Graves concluded that they were going to join forces at the Chesapeake. Sailing south with 19 ships of the line, Graves arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake on 5 September to see de Grasse's fleet at anchor in the bay. De Grasse hastily prepared his fleet, numbering 24 ships of the line, for battle and sailed out to meet Graves. In a two hour confrontation, the lines of the two fleets did not completely meet, with only the forward and center sections of the lines fully engaging. The battle was consequently fairly evenly matched, although the British suffered more casualties and ship damage. The battle broke off with the arrival of darkness.

For several days the two fleets sailed within view of each other, with de Grasse preferring to lure the British away from the bay, where de Barras was expected to arrive carrying vital siege equipment. On 13 September de Grasse broke away from the British and returned to the Chesapeake, where de Barras had arrived. Graves returned to New York to organize a larger relief effort; this did not sail until 19 October, two days after Cornwallis surrendered.

| “ | [The] Battle of the Chesapeake was a tactical victory for the French by no clearcut margin, but it was a strategic victory for the French and Americans that sealed the principal outcome of the war. | ” |

|

— Russell Weigley[5] |

||

Contents |

Background

During the early months of 1781, both British and American forces had begun concentrating in Virginia, a state that had previously not experienced more than naval raids. The British forces were led at first by the turncoat Benedict Arnold, and then by William Phillips before General Charles, Earl Cornwallis arrived in late May with his southern army to take command. In June he marched to Williamsburg, where he received a confusing series of orders from General Sir Henry Clinton that culminated in a directive to establish a deep water fortified port.[6] In response to these orders, Cornwallis moved to Yorktown in late July, where his army began building fortifications.[7] The presence of these British troops, coupled with General Clinton's desire for a port made control of the Chesapeake Bay an essential naval objective.[8][9]

On 21 May Generals George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau met to discuss potential operations against the British, considering either an assault or siege on the principal British base at New York City, or operations against the British forces in Virginia. Since either of these operations would require the assistance of the French fleet then in the West Indies, a ship was dispatched to meet with French Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse who was expected at Cap-Français, outlining the possibilities and requesting his assistance.[10] Rochambeau, in a private note to de Grasse, indicated that his preference was for an operation against Virginia. They then moved their forces to White Plains, New York to study New York's defenses and await news from de Grasse.[11]

De Grasse arrived at Cap-Français (now known as Cap-Haïtien) on 15 August. He immediately dispatched his response, which was that he would make for the Chesapeake. Taking on 3,200 troops, he sailed from Cap-Français with his entire fleet, 28 ships of the line. Sailing outside the normal shipping lanes to avoid notice, he arrived at the mouth Chesapeake Bay on August 30,[11] and disembarked the troops to assist in the land blockade of Cornwallis.[12] Two British frigates that were supposed to be on patrol outside the bay were trapped inside the bay by de Grasse's arrival; this failure prevented the British in New York from learning the full strength of de Grasse's fleet until it was too late.[13]

British Admiral George Brydges Rodney, who had been tracking de Grasse throughout the West Indies, was alerted to the latter's departure, but was uncertain of the French admiral's destination. Believing that de Grasse would return a portion of his fleet to Europe, Rodney detached Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood with 14 ships of the line to find de Grasse's destination in North America. Rodney, who was ill, sailed for Europe with the rest of his fleet in order to recover, refit his fleet, and to avoid the Atlantic hurricane season.[2]

Sailing more directly than de Grasse, Hood's fleet arrived off the entrance to the Chesapeake on 25 August. Finding no French ships there, he then sailed for New York.[2] Meanwhile his colleague and commander of the New York fleet, Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves, had spent several weeks trying to intercept a convoy organized by John Laurens to bring much-needed supplies and hard currency from France to Boston.[14] When Hood arrived at New York, he found that Graves, who had failed to find the convoy, was in port, but had only five additional ships of the line that were ready for battle.[2]

De Grasse had notified his counterpart in Newport, the Comte de Barras Saint-Laurent, of his intentions and his planned arrival date. De Barras sailed from Newport on 27 August with 8 ships of the line, 4 frigates, and 18 transports carrying French armaments and siege equipment. He deliberately sailed via a circuitous route in order to minimize the possibility of an encounter with the British, should they sail from New York in pursuit. Washington and Rochambeau, in the meantime, had crossed the Hudson on 24 August, leaving some troops behind as a ruse to delay any potential move on the part of General Clinton to mobilize assistance for Cornwallis.[2]

News of de Barras' departure led the British to realize that the Chesapeake was the target of the French fleet. By 31 August, Graves had moved his ships over the bar. Taking command of the combined fleet, now 19 ships, Graves sailed south, and arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake on 5 September, to see most of de Grasse's fleet anchored there.[2]

Battle

De Grasse had detached a few of his ships to blockade the York and James Rivers farther up the bay, and many of the ships at anchor were missing officers, men, and boats when the British fleet was sighted. Rather than directly attacking the French fleet at anchor, Graves ordered his fleet to form a line of battle aimed at the bay's mouth.[1]

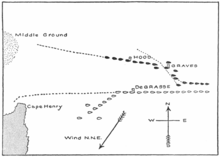

At 11:30 am, 24 ships of the French fleet cut their anchor lines and began sailing out of the bay with the noon tide, leaving behind the shore contingents and ships' boats.[1] By 1:00 pm, the two fleets were roughly facing each other, but sailing on opposite tacks. In order to engage, and to avoid some shoals (known as the Middle Ground) near the mouth of the bay, Graves then ordered his whole fleet to wear, a maneuver that reversed his line of battle, but enabled them to line up with the French line that formed as its ships exited the bay. This placed the division of Hood, his most aggressive commander, at the rear of the line.[15][16] It was after 4:00 pm, over 6 hours since the two fleets had first sighted each other, when the British—who still had the weather gage, and therefore the initiative—opened their attack.[16]

At this point, both fleets were sailing generally east, away from the bay, with winds from the north-northeast.[1] The two lines were approaching at an angle so that the leading ships of the vans of both lines were within range of each other, while the ships at the rear were too far apart to engage. The French had a firing advantage, since the lee gage meant they could open their lower gun ports, while the British had to leave theirs closed to avoid water washing onto the lower decks. Both sides were inconvenienced by crew shortages, the French because they had left their shore detachments behind. The French fleet, in addition to outnumbering the British in the number of ships and total guns, had heavier guns capable of throwing more weight, and thus had a decided advantage. Its state of repair was also somewhat better.[16]

The battle began with HMS Intrepid opening fire against the Marseillais, its counterpart near the head of the line. The action very quickly became general, with the van and center of each line fully engaged.[16] Graves made signals for the van to close, but also left signals for maintaining line of battle. Hood, directing the rear, interpreted the instruction to maintain line of battle to take precedence, and as a consequence his division never became significantly engaged in the action.[17] The British van took the brunt of the assault, and HMS Terrible, which was already in fairly poor condition, was badly mauled.[4] With the onset of darkness, firing ended and the two fleets disengaged.[18]

Aftermath

For several days after the battle the two fleets continued to maneuver within sight of each other, as ships on both sides carried out repairs.[19] De Grasse tried on several occasions to reengage the British, without success, all the while trying to make sure the fleets stayed away from de Barras' route.[20] French scouts spied de Barras' fleet on 9 September, and de Grasse turned his fleet back toward Chesapeake Bay that night. Arriving on 12 September, he found that de Barras had arrived two days earlier.[21] Graves, after learning that the two French fleets had successfully joined, scuttled the Terrible, and turned his battered fleet toward New York.[22][23] He arrived off Sandy Hook on 20 September.[22]

The French success left them firmly in control of Chesapeake Bay, completing the encirclement of Cornwallis.[24] In addition to capturing a number of smaller British vessels, de Grasse and de Barras assigned their smaller vessels to assist in the transport of Washington's and Rochambeau's forces from Head of Elk to Yorktown.[25]

After effecting repairs in New York, Admiral Graves sailed from New York on 19 October with 25 ships of the line and transports carrying 7,000 troops to relieve Cornwallis.[26] It was two days after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, an event that eventually led to peace two years later and British recognition of the independent United States of America.[27]

Memorial

At the Cape Henry Memorial located at Fort Story in Virginia Beach, Virginia, there is monument commemorating the contribution of de Grasse and his sailors the cause of American independence. The memorial and monument are part of the Colonial National Historical Park and are maintained by the National Park Service.[28]

Order of battle

| France (de Grasse) | Britain (Graves) |

|---|---|

| (Ship — guns, Commander) | (Ship — guns, Commander) |

Pluton – 74, Albert de Rions

César – 74, Coriolis d'Espinouse

Citoyen – 74, Ethy |

Alfred – 74, Captain Bayne

America – 64, Captain Thompson

Terrible – 74, Captain Finch — damaged, later scuttled |

|

(*) Van flag, Bougainville |

(*) Van flag, Samuel Hood |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Morrissey, p. 54

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Mahan, p. 389

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Castex, p. 33

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Morrissey, p. 56

- ↑ Weigley, p. 240

- ↑ Ketchum, pp. 126–157

- ↑ Grainger, pp. 44,56

- ↑ Ketchum, p. 197

- ↑ Linder, p. 15

- ↑ Mahan, p. 387

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Mahan, p. 388

- ↑ Ketchum, pp. 178–206

- ↑ Mahan, p. 391

- ↑ Grainger, p. 51

- ↑ Grainger, p. 70

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Morrissey, p. 55

- ↑ Grainger, p. 73

- ↑ Linder, p. 16

- ↑ De Grasse, p. 156

- ↑ De Grasse, p. 157

- ↑ De Grasse, p. 158

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Morrissey, p. 57

- ↑ Allen, p. 323

- ↑ Ketchum, p. 208

- ↑ Morrissey, p. 53

- ↑ Grainger, p. 135

- ↑ Grainger, p. 185

- ↑ National Park Service – Cape Henry Memorial

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy. Bohn. http://books.google.com/books?id=PVE2AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA25&lpg=PA25&ots=_3_TYdmZgm&sig=1Kjc8kVHhlXqIooni_eqtTZq3yI#PPA322,M1.

- Davis, Burke (2007). The Campaign that Won America. New York: HarperCollins.

- Castex, Jean-Claude (2004). Dictionnaire des batailles navales franco-anglaises. Presses Université Laval. ISBN 2-7637-8061-X.

- Grainger, John (2005). The Battle of Yorktown, 1781: a reassessment. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843831372.

- de Grasse, François Joseph Paul, et al (1864). The Operations of the French fleet under the Count de Grasse in 1781-2: as described in two contemporaneous journals. New York: The Bradford Club. OCLC 3927704. http://books.google.com/books?id=aO0_AAAAYAAJ&dq=grasse%20chesapeake%20graves%201781&lr=&pg=PA157#v=onepage&q=grasse%20chesapeake%20graves%201781&f=false.

- Ketchum, Richard M (2004). Victory at Yorktown: the campaign that won the Revolution. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 9780805073966. OCLC 54461977.

- Linder, Bruce (2005). Tidewater's Navy: an Illustrated History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781591144656. OCLC 60931416.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1890). Influence of sea power upon history, 1660-1783. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 8673260. http://books.google.com/books?id=eh0MAAAAYAAJ&dq=mahan%20naval%20power&pg=PA388#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Morrissey, Brendan (1997). Yorktown 1781: the world turned upside down. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855326880.

- Weigley, Russell (1991). The Age of Battles: The Quest For Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-7126-5856-4.

- "National Park Service – Cape Henry Memorial". National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/came/index.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

External links

- War for Independence—Battle of the Capes on u-s-history.com

- Center of Military History, Battle of the Virginia Capes

|

|||||||||||||||||||